Exhibition Soul of a Nation Art in the Age of Black Power January 6

Barkley Hendricks (American, 1945–2017). Claret (Donald Formey), 1975. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 72 x lone/2 in. (182.9 x 128.iii cm). Courtesy of Dr. Kenneth Montague | The Wedge Collection, Toronto. © Manor of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the creative person's manor and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum)

William T. Williams (American, born 1942). Trane, 1969. Acrylic on canvas, 108 x 84 in. (274.iii 10 213.iv cm). The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York. © William T. Williams. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York

William T. Williams began making "hard-edge" abstract paintings at Yale, where he studied with artist Al Held. This painting was named after jazz saxophonist John Coltrane and may conjure the cascades of sound in his performances.

Trane was made in New York in the aforementioned twelvemonth that Williams—as a member of the Smokehouse Associates—created a number of abstract wall paintings in Harlem. That twelvemonth he besides ready the artist-in-residence plan at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

Carolyn Lawrence (American, born 1940). Black Children Go on Your Spirits Free, 1972. Acrylic on canvas, 481/2 ten 501/2 x five1/4 in. (123 x 128 x 13.5 cm). Courtesy of the creative person. © Carolyn Mims Lawrence. (Photo: Michael Tropea)

Faith Ringgold (American, built-in 1930). United States of Attica, 1972. Offset lithograph on paper, 213/4 10 27ane/ii in. (55.2 x 69.9 cm). © 2018 Courtesy ACA Galleries, New York. © 2018 Faith Ringgold, fellow member Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Here, Faith Ringgold documented the 1971 uprising at Attica Prison, over demands for inmate rights, that left forty-three dead. The paradigm presents the Attica Prison house riot non as an isolated event but as an American tragedy to be understood within an ongoing, nationwide context. The caption reads: "This map of American violence is incomplete / Delight write in any y'all find defective."

At the top of its popularity, this print was circulated as 2 one thousand small-format posters. Ringgold first studied printmaking at the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/Schoolhouse founded by Amiri Baraka.

Roy DeCarava (American, 1919–2009). Couple Walking, 1979. Gelatin silver print on paper, 11 x 14 in. (27.9 x 35.6 cm). Courtesy of Sherry Tuner DeCarava and the DeCarava Archives. © 2017 Estate of Roy DeCarava. All Rights Reserved

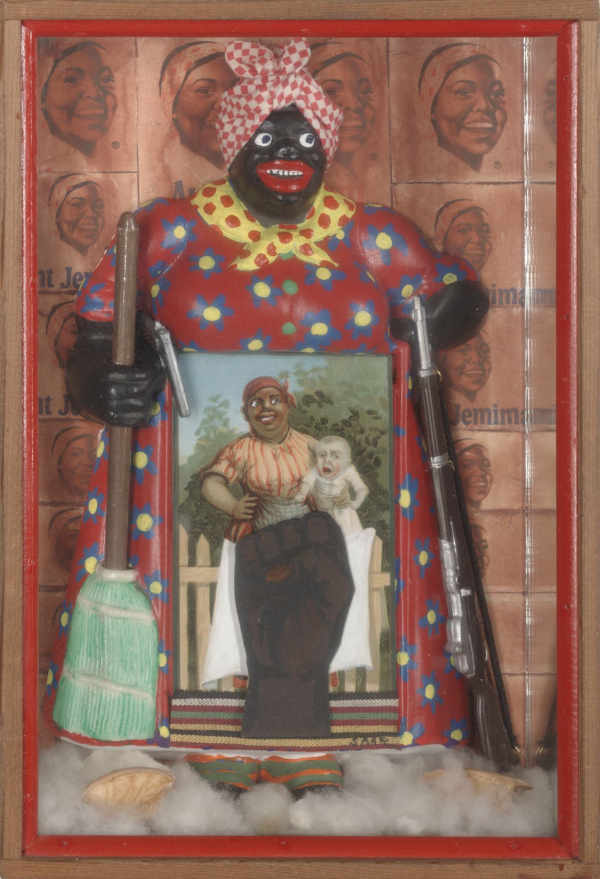

Betye Saar (American, born 1926). The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, 1972. Woods, cotton wool, plastic, metal, acrylic, printed newspaper and textile, 11iii/iv x 8 ten 23/4 in. (29.8 x xx.3 x vii cm). © Betye Saar. Drove of Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley, California; purchased with the aid of funds from the National Endowment for the Arts (selected by The Commission for the Conquering of Afro-American Art). © Betye Saar. (Photograph: Benjamin Blackwell. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles)

Perhaps Betye Saar'southward best-known work, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima juxtaposes radical Black Nationalist imagery of weapons, a raised fist, and African kente material with Aunt Jemima, the Southern "mammy" recognized as the confront of the best-selling pancake mix and a stereotype of smiling, docile servitude. Saar was appalled past racist depictions she establish on everyday objects at flea markets and in curio shops. Inspired in part by Joseph Cornell's Surrealist assemblages, here she incorporated a kitchen notepad holder in the course of a Black female figure. Moved by the force and determination of Blackness women, Saar sought to recast a painfully enduring prototype of Black female subservience equally a symbol of empowerment.

Alma Thomas (American, 1891–1978). Mars Dust, 1972. Acrylic on canvas, 691/4 x 571/8 in. (175.9 x 145.1 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from The Hament Corporation, 72.58. © Estate of Alma Due west. Thomas. (Digital epitome: © Whitney Museum, N.Y.)

Mars Dust was ane of a serial of paintings that Alma Thomas included in a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1972. At age eighty, she became the first African American adult female to have a solo show at that place. Fascinated by the technological advances of the space age, she looked at daily reports of NASA'southward Mariner ix mission to photo Mars. Huge grit storms on the planet, which initially prevented the relay of images back to World, inspired her to make this piece of work.

Frank Bowling (American, born 1936). Dan Johnson's Surprise, 1969. Acrylic on sheet, 116 ten 104one/8 in. (294.5 x 264.5 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from the Friends of the Whitney Museum of American Art, 70.xiv. © Frank Bowling. Image courtesy of the artist and Hales Gallery. (Digital image: © Whitney Museum, North.Y.)

In the late 1960s and early on 1970s, Frank Bowling's work drew from Color Field painting of the 1940s and 1950s, notwithstanding maintained representational images. He poured waves of acrylic over stencils of continents, which were removed earlier more paint was practical, leaving ghostly outlines. Continents emerge from and disappear into color; oceans and rivers are combined with pools and trails of liquid pigment. While many Black Americans were pointing to Africa as a mother continent, Bowling'south maps gloat a more fluid and open idea of identity and belonging in the world, enacting what scholar Kobena Mercer calls a "decolonial space of decentering." Texas Louise and Dan Johnson's Surprise were included in Bowling's solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in late 1971.

Built-in in Bartica, Guyana, Bowling moved to England in his teens. In 1966 he relocated to New York, where he joined a group of abstract artists and included many of them (such as William T. Willliams and Daniel LeRue Johnson) in his 1969 exhibition v+1 at the State Academy of New York at Stony Brook. This exhibition, and Bowling'southward extensive writings, argued for an expansive notion of Black art encompassing both abstract and figurative.

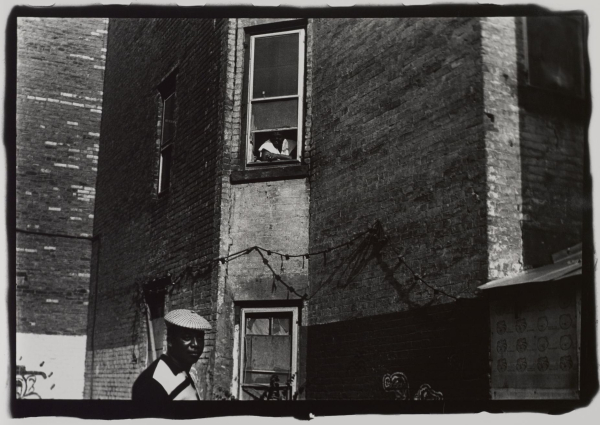

Ming Smith (American). When You Come across Me Comin' Enhance Your Window High, 1972. Vintage gelatin silver impress, eleven 10 14 in. (27.nine ten 35.6 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Steven Kasher Gallery. © Ming Smith

Source: https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/soul_of_a_nation

0 Response to "Exhibition Soul of a Nation Art in the Age of Black Power January 6"

Post a Comment